I acted like I could do everything without help—society told me I could anyway. You know the old phrase, “Pull yourself up by your bootstraps.” I looked up the origin of those words—it was thought to have come from a fictional story by German author Rudolf Erich Raspe. It talked of a nobleman who pulled himself out of a swamp by his hair.

Let me try that in a sentence:

“I’m gonna pull myself out of this swamp by my own hair and get that promotion.”

That seems to work. I think I like it.

Eventually, the phrase evolved and was understood as doing something without help, no longer attempting to rationalize an impossible task—I can’t pull myself up by my bootstraps; that’s absurd. I can’t deny the laws of physics and make myself levitate.

I’m not special but unique to the people around me. And so is my childhood.

I’m afraid to write down what’s in my head because my mother reads these writings religiously. I’m going to write about my childhood, and in childhood, we all have a caregiver, or model, that provides influence. Although obvious, influence can affect a child as they become an adult.

When I was 16, I was sent to the hospital. Within my skull, the blood in my arteries flowed straight to veins, where my capillaries should have been. The artery-to-vein transition burst, which caused blood to flow to my brain. This was an urgent situation, but I survived.

My parents began to shelter me and were protective of me because of this. How they dealt with the stress and anxiety they would go through, I’m sure, affected me as well. As the years rolled by, I never communicated with my family as I should have, most likely because I was afraid to. I would always redirect and talk about childish, schoolboy humor.

When I could gather myself, I would talk.

I learned my brother became worried the same would happen to him each time he had a headache—that he would have his own arteriovenous malformation.

I learned my brother, who was only 13 at the time, told my sister, who was around 7, that I might die.

I started having seizures two years after I left the hospital. When I was 21, I took a 69-year-old man’s life with a Pontiac Bonneville—I was unconscious when this happened. I learned my parents went through a dramatic situation when they visited the bereaved family.

I learned this was why my family left the church when persuasive rumors spread about the accident.

My parents did what they thought was best for me: letting me know what they believed was essential—to help me become strong and connected in my ever-changing environment.

I believed the darkness of these situations alone were me; I thought this was my makeup.

This affected me in many subconscious ways. As a simple example, I’d make self-deprecating remarks so I could hear people tell me those remarks aren’t true. “I’m only kidding,” I’d say to them.

I became who I thought I was through the stories I told myself. My stories were sad.

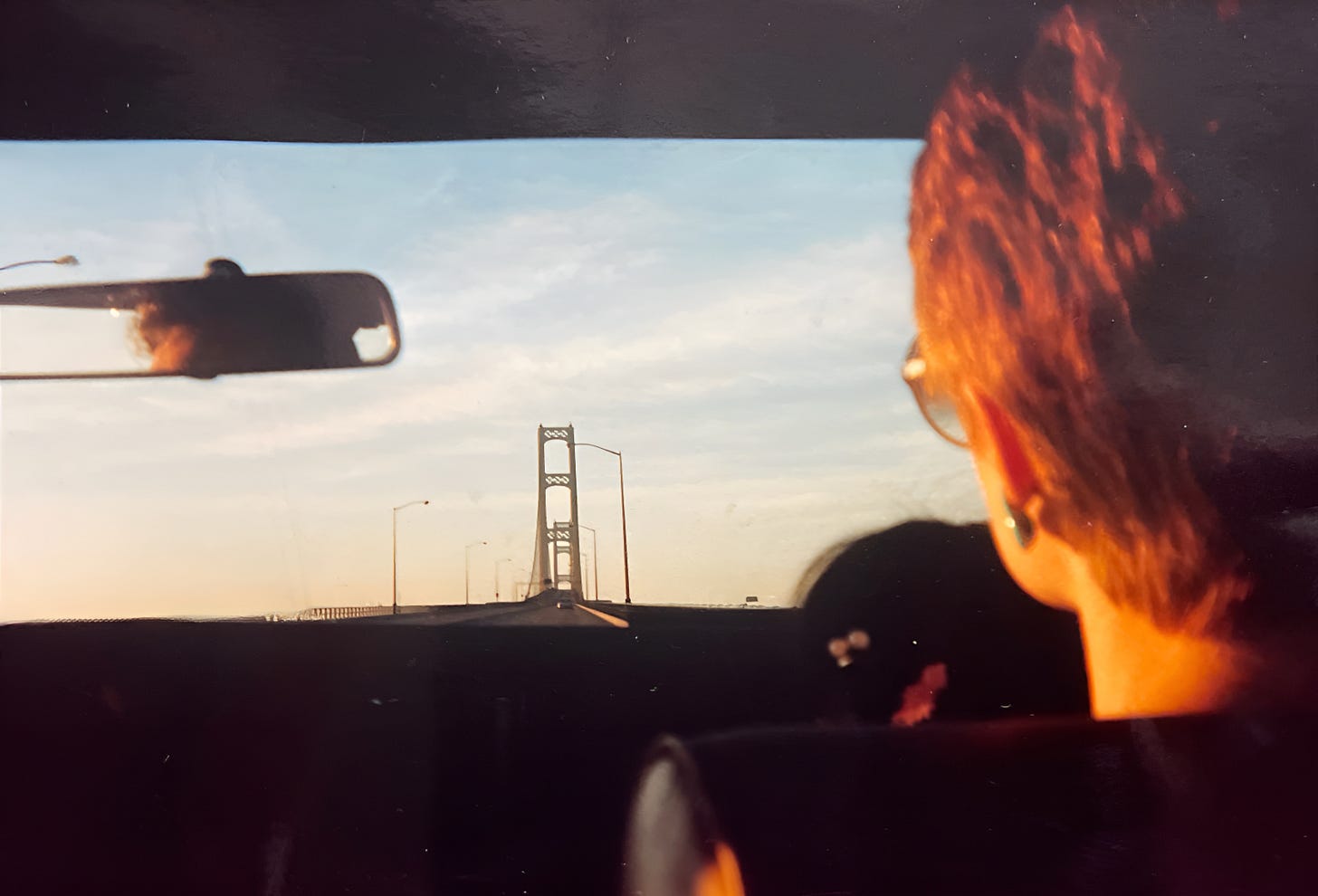

I was looking through a scrapbook of photographs from the late 80s I took when I was around 17 or 18. They were captivating—taken off center, faded, and blurry. But that gave them charm.

Some were taken when my brother and I stayed at our grandparents’ house. The only thing I can fully remember is my grandpa claiming that the local art train we went to look through was, as he put it, the “fart train.” I don’t recall the art, but my grandpa wasn’t impressed.

I have an image of my sister holding a mourning dove and another where she was crammed into a Grand Rapids Press newspaper bag—my brother having it strapped around his shoulder.

We took a trip to Mackinac Island, Michigan. Most of those images seemed to capture an emotion—seagulls flying overhead; one of the Mackinac Bridge I took from the back seat; and a canon firing over Lake Huron, giving out only large smoke plumes.

I lost my job a few months ago. I didn’t want to lose my job—I wanted to prove to myself that I could take it on and, at the same time, succeed at it.

As things went downhill, I purchased one of those lights that emulate daylight to help me wake up bright-eyed and bushy-tailed. I put up positive affirmations around the house—some long and ridiculous. I even had Alexa tell me historical facts at 5:50 in the morning, as I love a good historical fact.

They weren’t working, however.

I felt I could meet the challenge and do it on my own. But when I began to doubt myself, the people around me noticed. Some coworkers asked me if I wanted to do my job; I thought I did, but my confidence was slighted. If I admitted to anyone that I couldn’t do it, I feared they would believe me and tell me I shouldn’t be doing what I was doing. I felt isolated.

There were no accommodations—I was told I couldn’t be put in my original position because I’d then replace someone who already had that position. That wouldn’t be fair to them, I was told. I worked there for almost six years—I was left to my vices to find another job inside the organization.

I don’t blame anyone directly; it was a perfect storm.

Something was going on with my amygdala—the portion of the brain that holds emotional memories—and this wasn’t allowing me to be successful. I believe a memory or two were keeping me at bay.

The amygdala and hippocampus are part of the midbrain. This separates the lower and higher portions of the brain.

The brain’s primary job is to keep me safe. If I were to pick up a hot pan with my bare hands, I would feel pain and drop it—the brain’s response is similar. If I were to approach something that felt overwhelming and I was unable to escape it, it would mark those memories with neurochemicals. Years later, if I found myself in a similar situation, it would warn me to escape the danger through the best survival strategy: fight, flight, freeze, or fawn.

My past not only dictates my present experiences but keeps me in my lower brain, and I miss my best life, found in my higher brain.

The only way I can get to a point of success is with positive and supportive people around me. That isn’t always possible in stressful situations, but there should be accommodations for these challenges.

So what is my greatest weakness?

I can’t pursue goals without continuous support. This doesn’t make me weak; it makes me unique to the people around me. I’m learning; I need to let people know when I’m in a tight spot—when I’m sinking. But, at the same time, I shouldn’t be afraid that people will see me differently.

I’m starting over now, a little lower on the career ladder by society’s standards.

But that doesn’t matter, because…

I have a big idea, but as you might already know, I can’t do it on my own.

I want people to feel empowered by telling their stories.

I want people to feel free to ask for accommodations in the workplace without feeling like they are less than their coworkers.

I want these invisible conditions to be accommodated.

I plan to be at Steelcase to participate in the Better is Possible Design Challenge on October 25. The theme: Belonging. The challenge: How might we foster a sense of belonging where everyone feels seen, heard, and valued in the workplace and the world?

This idea fits that theme, and I want to let people know about it.

Subscribe to this publication to support me and, if you feel so inclined, become a paying subscriber to put that fire in my belly.

Please reply with a kind message or click the heart icon here or on any social media I’ve shared this with—engagement helps promote and get this article public and seen!

Follow along, and I’ll keep you updated.

Thank you for whatever support you can give. It’s appreciated.