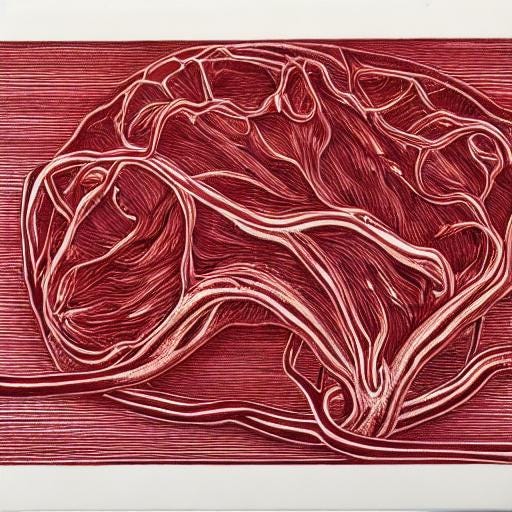

When I was 16, I had an arteriovenous malformation (AVM) that burst, causing blood to flow into my brain substance, in the subarachnoid space beneath the skull. This malformation is formed where the arteries transition to veins; in this transition are capillaries where gases are exchanged, and where nutrients and oxygen are spread into the tissues and organs of our bodies. But there are no capillaries in this malformation, so the blood flows rapidly, and can burst. My AVM wasn’t discovered until it was too late. I’ve now worked in different positions in the same healthcare system that once treated me when I was 16. When I was employed at the hospital as a nursing technician, I found myself getting pulled to different areas, and I searched the halls and rooms for the exact spot where I was treated. Maybe I found that defining space, I’ll never know—this was 24 years after the fact. But what was I looking for?

Jean Paul Sartre’s debut novel, Nausea is about Antoine Roquentin, a man who is writing a journal where he documents the strange sensations that he is feeling, something he terms as, the Nausea. In this novel, Roquentin is starting to realize that these feelings of Nausea are coming from the realization that he exists. Simply, Roquentin is becoming aware of who he is and of the people around him. And it makes him sick.

At one point, Roquentin finds himself in a bar and is overcome with anxiety. He asks the barmaid to play one of his favorite songs, Some of These Days. Before the song begins he worries that nothing in the song will be a surprise to him as he will only anticipate each note and lyric, the same notes and lyrics he’s heard so many times before. But when the song does begin, his anxiety vanishes. The melody crushes time, making him feel inside the music. The song arrested his thoughts.

“What has just happened is that the Nausea has disappeared. When the voice was heard in the silence, I felt my body harden and the Nausea vanish. Suddenly: it was almost unbearable to become so hard, so brilliant. At the same time, the music was drawn out, dilated, swelled like a waterspout. It filled the room with its metallic transparency, crushing our miserable time against the walls.”

Roquentin realizes he’s writing his journal to give him an awareness of not who he is, but who he was. He finds that he can be free in the midst of his circumstances and this makes him anxious, but seeking music allows this anxiety to swell into nothingness. By the end of the novel he finds he can survive his anxiety by ignoring it and by distracting his mind to better things. As Sartre wrote, “Life begins on the other side of despair.”

There is a mural that is on a concrete structure, north of the hospital, just beyond a highway. Following the surgery for my AVM, I recovered nicely. After a week of laying in bed, I was able to get up and push myself around in a wheelchair. I was bored, wandering the halls as the nurses busied themselves to call lights and sat behind their desks, staring at sheets of paper. I recall looking out at that mural from the hospital window one morning. I remember staring at this mural vividly because I did it for some time. The mural was designed by artist Russ Brown and depicts the city's history from 1826 to 1930. It has the artist’s rendition of Louis Campau and his wife Sophie, a horse-drawn fire engine, and a Grand River steamboat. When I roamed the halls as a hospital employee, 24 years later, I looked for this spot just as I had looked for the spot that defined my youth. I found a few public areas where someone in a wheelchair could see out to where the mural was. There is something about being in the same place, many years later, that helps me visualize where I was at that point to where I am today. It gives me a sense of melancholy, and the entire stretch of time between those two points is erased. As I stood there I started to romanticize that moment—I was becoming aware of who I had been.

I now work in an operating room. Here, I approach the job with the purpose already there: keep the field sterile, pass off the instruments with commitment, and read the specimen container before passing it off. When I approach something with a sense of I need to get this done, I have no time to think about anything else. I need to find a purpose to discover who I am, and then find satisfaction in that.

Now, as I’m writing this, something profound has happened. Absolutely nothing: no expectations, no anxiety, no frustrations, no worries. This is the art of action and for me, the art of writing. I need to do something with myself that crushes time against the wall; something that keeps me in the moment; something that arrests my thinking self. My purpose doesn’t always have to be the right purpose—it can be anything, so long as I commit to it.

*Here fades in Some of These Days, by Ethel Waters*

“crushing our miserable time against the walls”!!! Music gives the space for a heart to grow!