A nurse asked if I would help lift a patient in room 4. Sometimes patients would scoot down in bed from the occasional moving around they would do. I followed the nurse into the room and I noticed an older, obese woman, staring at the ceiling. The nurse went to one side and I to the other. We grabbed the straight sheet as she counted to three, then hoisted her up. She barely moved. I grabbed a firmer grip as we were about to hoist her again, and the patient took her hand and started to scratch at me. The nurse told her, “Please, stop—we are only trying to help you”. We attempted again without much improvement. We left it as it was—I walked to a chair and recorded notes on a computer. Ten minutes later, I noticed a commotion coming from room 4. I walked over and saw the nurse on top of the patient, giving her chest compressions. There was a nurse tech beside me, “Now’s your chance—go ahead and help.”

I had just started working in the emergency department, and I was learning the ropes, slowly gaining respect. I’ve never given chest compressions before, but here was the chance to do it; I trained for this. As she continued giving compressions a male nurse waited to relieve her, for when she grew tired. I walked behind him. When my time came, I stood on top of the stool, put myself in position, hands interlocked, and started compressing (two inches deep, to the beat of Staying Alive.) As I gave compressions, I observed, amidst the chaos, an anesthesiologist attempting to fit her with a laryngoscope to open her airway. The laryngoscope had a small monitor attached to it and I saw that the anatomy of the throat could barely be recognized as it was red with blood. I continued compressions as the crash cart behind me announced that I wasn’t compressing fast enough. I had the next person in line relieve me—I suddenly felt the urge to urinate. When I came back from the bathroom, the patient was being wheeled to ICU.

This was one month prior, before Covid-19 became a pandemic. This was before everyone was wearing a mask 24/7. The nurse said that the patient must have had the virus. I have not yet tested positive for Covid-19 despite, at the time, working in an emergency department. Maybe I was lucky.

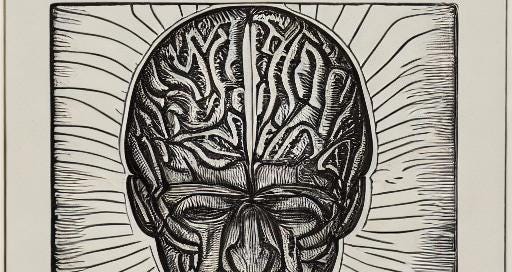

After being hospitalized for my arteriovenous malformation (AVM), I started my freshman year in high school. The transition from middle school to high school, right after having an AVM, was difficult. I remember, in the first weeks of classes, walking with another classmate as we left school, and he asked me, “How was it? Did you see the light?” No, I had not. He was genuine when he asked it, but I think I was numb to everything at that point. Recently, I was apprenticing as a surgical technologist, and I overheard a surgeon talking about near-death experiences and how these people saw the light. He said, “We know what our hardware is doing, but we don’t know what our software is doing.” This seemed drenched in symbolism, and it fascinated me. I believe he was implying that we know what our active selves are doing, but we don’t know what our spiritual selves are doing. Most people, who have witnessed a near-death experience, explain the light as an overwhelming sense of peace and well-being—it’s not just a light bulb at the end of a tunnel. And they come back from their experience to explain this feeling.

Two years later, after my AVM, I began having seizures. Before those seizures, I would have an aura (or focal aware seizure). For me, an aura felt like I was in a dream state: an intense sense of joy with detachment; a feeling of deja vu. I feel this is similar to seeing the light. Most likely, these feelings are just the brain misfiring. But why is the brain misfiring at that very moment? Is it telling us of something that might happen? Is the light experienced as just that—a misfiring brain? Maybe that’s what luck is, too.

Prince Myshkin, a character from Fyodor Dostoevsky’s book The Idiot, had epilepsy. Dostoevsky, who suffered from the same, described what Myshkin’s onset of a seizure would feel like.

“He was thinking, incidentally, that there was a moment or two in his epileptic condition almost before the fit itself (if it occurred in waking hours) when suddenly amid the sadness, spiritual darkness and depression, his brain seemed to catch fire at brief moments. […] His sensation of being alive and his awareness increased tenfold at those moments which flashed by like lightning. His mind and heart were flooded by a dazzling light. All his agitation, doubts and worries, seemed composed in a twinkling, culminating in a great calm, full of understanding […] but these moments, these glimmerings were still but a premonition of that final second (never more than a second) with which the seizure itself began. That second was, of course, unbearable.”

I am not belittling spirituality if I were to call it a misfiring brain; maybe I should say that our brains need to be rewired to attain it. Luck, like spirituality, is out of our control. I believe luck is when we have been challenged by adversity, and now we seek its meaning. Luck is our sense of hope; we should always be in luck.

Side note: I haven’t had a seizure in several years; they are now controlled by medication.